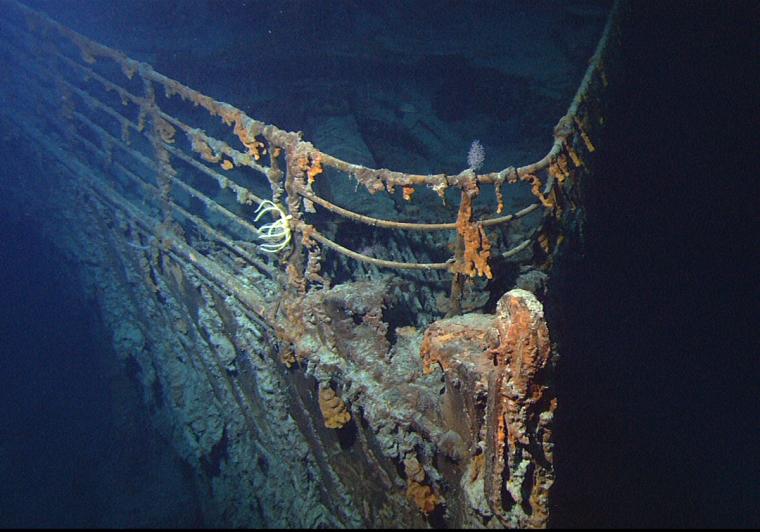

View of the bow of the RMS Titanic photographed in June 2004 by the ROV Hercules during an expedition returning to the shipwreck of the Titanic.Courtesy of NOAA/Institute for Exploration/University of Rhode Island (NOAA/IFE/URI).

It was less than a year ago that a submersible exploring the wreck of the Titanic imploded, killing all five passengers who were on board, including Stockton Rush, the CEO of OceanGate, the company that manufactured the submersible and ran the operation.

What followed that was a combination of anger, recriminations and threatened lawsuits. OceanGate has since suspended all exploration and commercial operations, although parts of the website for its foundation can still be viewed. And a few people who had previously made the trip with OceanGate to see the Titanic remarked on the danger involved, and noted they would never venture there again. The wreck of the Titanic, the said, should be left in peace. (Last month, ABC News reported on OceanGate's battle with a whistleblower, who repeatedly warned officials the submersible was not safe, but had his claims dismissed.)

A recently released interview of Rush included his joking remark, "What could go wrong?" with regard to the exploration.

But already, another company is trying to explore the wreck, starting this year. This time, the U.S. government has filed a motion to stop it, citing a law that protects and preserves the shipwreck as a gravesite.

The wreckage of the Titanic was originally discovered in 1985 by a joint French-American expedition led by Jean-Louis Michel of IFREMER and Robert Ballard of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. The ship, which sank in April 1912, was located two miles below the surface of the North Atlantic Ocean, on the Canadian continental shelf.

Originally recognizing the value and historical significance of the wreck, and as a precaution against harm or physical altering that could be caused by those who wanted to glean artifacts, Congress passed the Titanic Memorial Act in 1986. The act directed the State Department and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (which is under the Department of Commerce) to negotiate an international agreement, which entered into force in 2019.

This is where it gets sticky. According to CNN, RMS Titanic Inc. (RMST, as it has become known in court filings) obtained the salvage rights through an order entered by the US District Court in Norfolk, Virginia, in June 1994. RMST said in a periodic report filed this June that the company is planning an unmanned 2024 expedition but does “not intend to seek a permit,” according to the motion filed by the U.S. government. (The U.S. government says it needs one.)

RMST makes a business of showcasing artifacts that have been retrieved from the wreck, ranging from silverware to a segment of the Titanic's hull. Over the course of several years, it has removed thousands of items from the wreckage site. One of RMST’s key officers was French explorer Paul-Henri Nargeolet, who served as the company's director of underwater research. Nargeolet, who earned the moniker, “Mr. Titanic,” was one of those killed in the Titan submersible disaster in June.

Continued exploration of the site is what “Nargeolet would have wanted,” RMST personnel told reporters at Business Insider.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, “the government argued that the Secretary of Commerce’s permission is needed for operations that would physically disturb the wreck, citing federal law and an agreement between the U.S. and Britain. The company disagrees, arguing that it doesn’t need federal approval to carry out a planned expedition to the wreck. The case is playing out in the U.S. District Court in Norfolk, Virginia, which specializes in shipwreck recovery and which ironically granted the company salvage rights nearly three decades ago, according to the New York Times’ William J. Broad.”

The question at the heart of the matter: Who controls access to the wreck? The argument hinges not only on federal law in the U.S. but on a pact with Great Britain to treat the sunken ship as a memorial to the more than 1,500 people who died.

PBS News notes: “The U.S. argues that entering the Titanic’s severed hull, or physically altering or disturbing the wreck, is regulated by federal law and its agreement with Britain. Among the government’s concerns is the possible disturbance of artifacts and any human remains that may still exist.”

“RMST is not free to disregard this validly enacted federal law, yet that is its stated intent,” U.S. lawyers argued in court documents. They added that the shipwreck “will be deprived of the protections Congress granted it.”

RMST’s expedition is tentatively planned for May 2024; the company is countering the government’s argument, stating that its plans include photographing the entire Titanic, including areas “inside the wreck where deterioration has opened chasms sufficient to permit a remotely operated vehicle to penetrate the hull without interfering with the current structure.” It also wants to retrieve objects it finds in the debris field and “may recover free-standing objects inside the wreck.” Those could include “objects from inside the Marconi room, but only if such objects are not affixed to the wreck itself.”

The Marconi room holds the ship’s radio, a Marconi wireless telegraph machine, used to broadcast the Titanic’s increasingly frantic distress signals following the ship’s collision with an iceberg. The messages in Morse code were picked up by other ships and onshore receiving stations, helping to save the lives of about 700 people who fled in life boats.

“At this time, the company does not intend to cut into the wreck or detach any part of the wreck,” RMST stated.

Pundits say that is RMST’s way of sidestepping the question; if the radio can be lifted without being cut free, RMST is likely to take it and exhibit it.

RMST’s quest for the Titanic’s radio is well known to the government; in fact, RMST seems to view the radio as a holy grail. In 2020, CNN reports, RMST said they wanted to recover the radio, a request that was granted in May 2020 by a U.S. district judge. In that filing, the court stated they found that the company’s plan “seeks to minimize disturbance to the rest of the Titanic wreck, including to the hull of the ship and the remains of those 1,500 souls lost in the sinking of the ship.” The US government, however, filed a legal challenge to stop that planned mission, which ultimately never happened.

Shipwreck tourism is a hardy perennial, and underwater tourism, the collective term for submersibles, snorkeling and SCUBA, is offered in multiple locations. While an enormous number of states have wrecks – and many are able to be seen by the public (yes, even in landlocked states like Arizona), some dive sites are more spectacular than others. Additionally, diving and snorkeling provide opportunities to learn about marine life, conservation and even water and boating safety.

An enormous part of the Outer Banks’ tourist appeal, in fact, comes from its reputation as the Graveyard of the Atlantic, with its dangerous shoals and frequently rough waters contributing to more than 5,000 ships sunk in that area since the 1500s, with the most recent being 2012 during Hurricane Sandy. (The area around Cape Hatteras alone is home to more than 600 wrecks.)

On the opposite side of the country lies the Graveyard of the Pacific, a stretch of the coastal region in the Pacific Northwest, from Tillamook Bay on the Oregon Coast northward to Cape Scott Provincial Park on Vancouver Island. The unpredictable weather conditions and coast characteristics have caused more than 2,000 shipwrecks in the area.

Another emerging area of wreck interest is that of slave ships, as detailed in this article about The Slave Wrecks Project.

Of course, there is also the storied Bermuda Triangle, an area in the western part of the North Atlantic Ocean, where the list of lost aircraft and ships is the stuff of legend. (Some take it one step further and categorize it as urban legend but either way, the area has fascinated shipwreck, history and mystery fans for years.)

Just in the past month, two shipwrecks have made headlines. In Cape Ray, Canada, a headland located at the southwestern extremity of the island of Newfoundland, a wreck was unearthed by a ferocious storm; so far, little is known about it but with archeologists on the scene, more information is bound to emerge. In Lake Superior, wreckage found about 600 feet down has been positively identified as that of the SS Arlington, a 244-foot bulk carrier that sank in 1940. And in January, in Acadia, Maine, a storm surge provided tourists with a rare view of the 112-year-old shipwreck of the two-masted schooner Tay.

And for those who have the shipwreck bug but want to stay on dry land, there’s always the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum (GLSHS) in Paradise, Michigan, on N. Whitefish Point Road. And if the term, Whitefish, sounds familiar to wreck devotees, there’s a reason: Whitefish Bay was mentioned in the Gordon Lightfoot song, The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. Those who want to get a little closer to that wreck, without having to go underwater, can see the ship’s 200-pound bronze bell (the one that rang 29 times, in memory of each man lost in the November 10, 1975 shipwreck). The bell was recovered from the wreck by divers in 1995.

The Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society (GLSHS) has conducted three underwater expeditions to the wreck, 1989, 1994, and 1995. In 2024, the GLSHS’s annual Edmund Fitzgerald memorial event will be offered as a livestream ceremony.