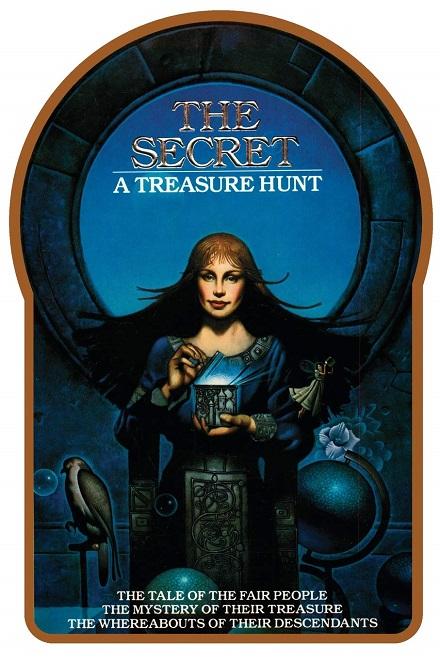

In 1982, children’s author Byron Preiss published The Secret, about a mythical treasure and its guardians—magical creatures hidden from human view. This vast universe of creatures existed solely in Preiss’s imagination – but the treasure was real.

Prior to the book’s release, the writer concealed 12 ceramic keys in hand-painted casques, then buried them in public parks around the U.S. Each key could be returned to Preiss in exchange for precious jewels, collectively worth around $10,000.

But, writes Atlas Obscura, Preiss’s treasure hunt had a problem: The treasure was simply too well hidden. Seekers found it nearly impossible to unravel the rhyming riddles and elaborate paintings that mapped the location of the casques. In the nearly 40 years since the book’s first publication, only two of the treasures have been found. No one knows exactly where the remaining casques are buried.

And before you ask, Preiss can’t help either; he died in a traffic accident in 2005.

The one thing we do know, however, is that the hunt has been bringing people to public parks in order to search. After all, the first casque was found by three teenagers in Chicago’s Grant Park. The second was located next to a wall marking the perimeter of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens. And treasure hunters seem certain yet another is located in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, although there have been multiple digs, all of them fruitless.

But nothing captures the imagination of the public like a riddle that can’t easily be solved. It’s the reason Stonehenge is popular, and the reason the Titanic remains fascinating after all these years.

The oddest part of all: all this searching just might help turn people on to other outdoor quest-related sports events.

Geocaching, the outdoor recreational activity, in which participants use GPS technology to seek out containers worldwide, is one example. Orienteering, in which participants use a compass and map to navigate between control points in unfamiliar territory, is actually a competitive sport. Trail running, mountain biking and camping, fishing and open water sports may also see a benefit.

So the question becomes: how can parks and event owners take advantage of the wave of treasure hunters and use them to bring new treasure hunters into the outdoors, and into the world of competitive sports? Hosting clinics that use entry-level routes and skill sets could help get some new visitors into parks, and could even help switch on even more interest in sports like orienteering. After all, with competitive climbing coming to the Olympics, it’s likely there will be an uptick of interest in outdoor pursuits – and orienteering (and geocaching) could prove attractive to those who don’t have climbing skills, or who want to explore the area, period. For children, scavenger hunts in parks and in other outdoor areas can help create a fun activity that keeps kids interested and engaged. Riverside Citrus State Historic Park in California has already done this, creating a mobile app, Tag Hunt, to help visitors explore the park in a scavenger hunt format.

Event owners who want to tie in interest in local treasure hunts – either high-profile or entry-level – will find a ready supply of stories and possibilities. A wealthy art collector named Forrest Fenn (alas, also now deceased) buried gold collectibles worth up to $10 million in a chest somewhere in the American Rockies around 2010. The hunt has been on ever since, and it remains popular, with multiple message boards, websites, social media pages and other forums devoted to it. And, unfortunately, it is a reminder of what can happen when adequate safety precautions are not taken in the wild; at least four people have died looking Fenn’s treasure, falling from heights and drowning in the fast-flowing rivers.