In Wisconsin, plans for a new university football practice field have hit a snag in the form of public pushback because the venue will obliterate a memorial park meant to honor soldiers.

Athletic Business reported that the University of Wisconsin is currently at odds with veterans, descendants of veterans and other officials who do not want to see the school develop athletic facilities on the site of what was once Camp Randall.

Badger Extra adds that will be the third time the school has taken land from the park in order to expand its athletic facilities; this happened in 1954 and again in 1986. Veteran-organized groups say they are tired of being pushed aside by the university in its march for expansion.

Camp Randall was used a training ground for more than 70,000 Union soldiers between 1861 to 1865; in 1862 more than 1,200 Confederate prisoners of war were detained on the site, making it the "single most important Civil War historic site in the state of Wisconsin," said Jason Maloney, the former chair of the state Board of Veterans Affairs.

The university has said it will take steps to honor Wisconsin veterans in exchange for the land. Badger Extra notes, “The university also committed to between $300,000 and $400,000 in one-time funding on veteran initiatives and an estimated $55,000 annually to fund a new position in the veterans services department. The athletic department will institute a program to recognize a veteran at each home football game and will install a seat at Camp Randall Stadium to recognize prisoners of war and soldiers missing in action. Tailgating in Camp Randall Memorial Park on football game days also will be halted.”

A few other initiatives are being studied and while veterans’ groups consider them a step in the right direction, they fear that in this year and in years to come, university will not stop obliterating the park until there is nothing left.

A few other initiatives are being studied and while veterans’ groups consider them a step in the right direction, they fear that in this year and in years to come, university will not stop obliterating the park until there is nothing left.

The section of the park that will be developed for the new facility is the "most valuable bit of real estate on the whole park," said Jim Gingras, a member of the university's chapter of Student Veterans of America. And he told Badger Extra, it is the only remaining part that's actually within the perimeter of what was Camp Randall during the Civil War.

But it’s not the first time land has been chosen for a sports facility, only to have developers and owners wrestle with problems caused by previously undiscovered, well, residents of that land. In December, construction workers in Indiana who were doing preliminary excavation work at the site of the new soccer stadium to be used by Indy Eleven had a grisly surprise: hundreds of human remains. Through investigation, it was discovered that the site covered four historic cemeteries (including the city’s first public cemetery, built during segregation) dating back to the 19th century.

Who owns the remains, how they should be handled and what should be done with them has ignited a fierce debate.

Mirror Indy reported, “The situation shines a light on the limitations of state and federal regulations to preserve historic cemeteries. Federal laws are only triggered when a federal agency or funding is involved, which is not the case with [stadium development company] Keystone’s project. And while state law requires archaeological plans to be filed with the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, it does not mandate a full excavation.

According to the plans, when human remains are found, work will stop and the remains will be documented and excavated by hand before construction continues. That falls short of the demands of community members, who are advocating for a proactive archaeological dig on at least a portion of the site to find and carefully exhume remains.

City officials say such a dig is impractical if not impossible, due to the long history of development at the site and the absence of headstones or records that would indicate where people are still buried.”

Indy is hardly alone in its discovery and the problems surrounding it. WRAL.com did a documentary, entitled “Ghosts in the Stadium,” exploring the times sports development has taken place around and even on top of historical sites, including cemeteries.

WRAL reporters note, “NC State's Carter-Finley is built atop a lost Black community, known as Lincolnville, and for decades crowds walked right past a hidden Black cemetery without even realizing it. The football stadium at UNC is linked to the brutal history of the Wilmington Massacre.”

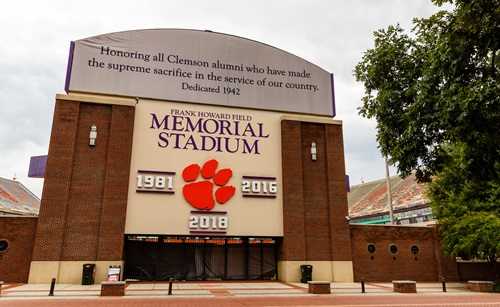

Additionally, the article notes, “For many years, football fans at Clemson University parked their vehicles and tailgated right in the middle of a burial ground – many never even realizing there were hundreds of people buried right beneath their feet. More than 500 unmarked graves dating back to the early 1800s serve as the final resting place for enslaved men and women – many who built the university itself, and before that, the plantation on which the school sits.”

Sometimes, even having a stadium close to a cemetery creates problems. ESPN reported on the University of Alabama, and the fact that Bryant-Denny Stadium is located right across the street from Evergreen Cemetery, which built in the 1830s. The placement “has made expansion and renovation tricky around the stadium. Moving cranes to work on the south end zone has been problematic. While the land itself is worth a king's ransom, no one dares consider building upon it.”

Other examples include:

Virginia: A high school football stadium in Prince William was under development when workers discovered human remains; upon further investigation, the site had once held a pre-Civil War-era graveyard. All remains were recovered and removed to a new cemetery.

Virginia: A high school football stadium in Prince William was under development when workers discovered human remains; upon further investigation, the site had once held a pre-Civil War-era graveyard. All remains were recovered and removed to a new cemetery.

New York: In Buffalo, outside Gate 7 of the Bills stadium, is a tiny graveyard – the Sheldon Family Cemetery, dating back to the early 1800s. And when the stadium was being developed, plans would have put those graves beneath the 50-yard line. Relatives and historians interceded – and so did then-Bills owner Ralph Wilson. The cemetery (in which nobody has been buried since the 1940s) is fenced off to keep out unwanted foot traffic, and still can be seen clearly. But not all history was honored; the ruins of a Native American settlement are located under the stadium.

Louisiana: In 1971, when the Superdome was being built, workers found remains and learned they were digging up what had once been the Girod Street Cemetery. Although the cemetery had been deconsecrated decades prior and all remains were supposed to have been moved to other cemeteries, enough had been left behind to give workers a scare. (A local superstition alleges that the notoriously poor record of the New Orleans Saints for many years was somehow supernaturally tied to the ground on which the dome was constructed.)

Florida: In 2021, it was reported that three possible graves had been found under a pair of parking lots adjacent to Tropicana Field, the home of Major League Baseball’s Tampa Bay Rays. The lots, though not on Tropicana Field itself, were built on the former site of Oaklawn Cemetery, which housed the remains of black people and white people in segregated sections.

“While the number of potential graves discovered is small, it is not insignificant,” St. Petersburg Mayor Rick Kriseman told the New York Post. “Every person has value and no one should be forgotten. This process is of the utmost importance and we will continue to do right by these souls and all who loved them as we move forward.”

The use of ground-penetrating radar has allowed for the examination of land if cemeteries are suspected to be present but it is a time-consuming, exacting and expensive process, involving the use not only of special equipment but of trained operators. (GPR cannot be used from a plane; it must be pushed directly over the ground slowly and carefully, with an eye to the readings). As a result, there needs to be a compelling reason for a developer to want land examined via GPR.

Sometimes, it’s nobody’s fault that cemeteries aren’t discovered until construction starts when records are lost to time. Particularly in the cases of the burying grounds of enslaved or very poor people, formal headstones did not exist. Without the tools for engraving and without the ability to read and write, many families used pieces of local stone or hand-made wooden crosses to mark the resting places of their loved ones. And in many cases, these cemeteries were never incorporated.

Another way graves would be neither recorded nor marked is in cases where people had to move along quickly, such as was the case when settlers were traveling by covered wagons. According to the National Park Service, the route of the Oregon/California/Mormon Pioneer Trails alone has been called "the nation's longest graveyard." Nearly one in 10 emigrants who set off on the trail did not survive. On-trail risks included rattlesnake bites, infection, drownings, lack of sanitation, disease, complications from birth in transit and exposure to the elements (not to mention violence from other settlers and indigenous people). In almost every case, settlers simply buried their dead along the trail (with little ceremony) and moved on.

The burial grounds of indigenous people also went unnoticed unless a nearby settlement alerted researchers to their presence. In the case of the Buffalo Stadium (an architectural dig spurred by the presence of the cemetery alerted historians to the presence of a tribal area), a member of the “Bills Mafia,” who had the advantage of her Native American ancestry, held a ceremony to lay her ancestors to rest. She burned tobacco, sage, sweetgrass and cedar traditional medicines meant to banish bad spirits. In an interview later, she said it was the least she could do to offer her well wishes and give the spirits back to the earth.

The burial grounds of indigenous people also went unnoticed unless a nearby settlement alerted researchers to their presence. In the case of the Buffalo Stadium (an architectural dig spurred by the presence of the cemetery alerted historians to the presence of a tribal area), a member of the “Bills Mafia,” who had the advantage of her Native American ancestry, held a ceremony to lay her ancestors to rest. She burned tobacco, sage, sweetgrass and cedar traditional medicines meant to banish bad spirits. In an interview later, she said it was the least she could do to offer her well wishes and give the spirits back to the earth.

But as society becomes increasingly landlocked, developers will have to confront long-forgotten cemeteries (or at least forgotten garves), as well as other sites of historical significance. There is a marked contrast between the activity and celebrations found in sports venues, and the solemnity and stillness of cemeteries and historical areas. Sports venues make money, cemeteries struggle to keep the grass mowed – and the fact that the latter have been bulldozed in favor of the former is, to some, a sad commentary.

"It makes you wonder, how much of America – the parts that we prize the most – were not only built on the backs of the people who built them, but literally were built on their graves, on the places where they died," historian and author Carmen Cauthen said to WRAL.